Disclaimer:

This essay acknowledges Sean Combs's profound role in creating Ready to Die, one of hip-hop's most significant albums. However, recent allegations against Combs, including federal RICO charges and sex trafficking, are deeply troubling and reprehensible. I stand in solidarity with his victims and unequivocally reject any form of violence, mistreatment, exploitation, or intimidation. This essay is intended for educational, cultural, and political thought and does not condone or excuse harmful actions by anyone, regardless of their contributions to art or culture.

The Notorious B.I.G.'s 1994 debut album, Ready to Die, is a landmark in hip-hop history, offering a raw portrait of urban life through masterful storytelling and wordplay. This essay explores the album's themes of criminology, poverty, mental health, street violence, and drug culture, along with its ethical underpinnings. I present an incisive analysis of this defining moment in hip-hop by contextualizing Ready to Die within Black New York history, particularly Jamaican and Caribbean immigrant communities.

Ready to Die's roots lie deep in Black New York's historical fabric. Christopher Wallace, born to Jamaican immigrants in Brooklyn, emerged from a city shaped by racial inequality, economic disparities, and cultural movements. From the Harlem Renaissance to Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, New York was a vessel of Black cultural and political life. Caribbean immigrants further enriched this tapestry, bringing new artistic dimensions to the city.

The 1960s saw the rise of the Black Power movement, with figures like Malcolm X deeply impacting Black youth. However, by the 1980s, urban Black communities faced economic disinvestment, gentrification, and the drug trade. Reagan-era policies, particularly the "War on Drugs," led to mass incarceration and increased policing in inner-city neighborhoods.

Hip-hop emerged in this context, providing an outlet for young Black and Latino voices. As the genre evolved, it became a platform for political expression and a commercial powerhouse. By the early 1990s, West Coast gangsta rap dominated the scene, leaving East Coast rap struggling to reassert itself.

Christopher "Biggie Smalls" Wallace, born May 21, 1972, was a product of Brooklyn's tough streets. His life of hustling and drug dealing, as well as his refuge in rap music, informed his artistry. Cheo Hodari Coker's biography Unbelievable recounts Biggie's journey from hustler to rapper, culminating in his signing with Sean "Puffy" Combs' Bad Boy Records.

Ready to Die was created during a critical moment for East Coast rap, as Combs aimed to reestablish New York's prominence in the face of West Coast dominance. Under Combs' leadership and with producers like DJ Premier and Easy Mo Bee, the album became a raw reflection of Brooklyn's harsh streets. Biggie's autobiographical lyrics dig into themes of poverty, crime, violence, mental illness, and existentialism, marking the album as a personal narrative and broader social commentary.

The opening song, “Things Done Changed,” reflects the societal shift in the streets of New York City, where B.I.G. grew up. Biggie recalls a time when things were less violent. But he describes how crime and violence have become more pervasive in the neighborhood: “Little motherfuckers with heat wanna leave a nigga six feet deep / And we coming to the wake / To make sure the crying and commotion ain't a motherfucking fake / Back in the days our parents used to take care of us / Look at 'em now, they even fucking scared of us / Calling the city for help because they can't maintain / Damn, shit done changed!” The song critiques the escalation of street violence, emphasizing a breakdown in community and family structures, leading to a survival-of-the-fittest mentality. Fittingly, this song resonates with doom-ism, a pessimistic view of the future. Biggie's tone conveys resignation to the violent culture he finds himself in, where death and crime are inevitable. In his final verse, Biggie raps, “Shit, it's hard being young from the slums / Eating five cent gums, not knowing where your meal's coming from / And now the shit's getting crazier and major / Kids younger than me, they got the Sky brand pagers / Going out of town, blowing up / Six months later, all the dead bodies showing up / It make me wanna grab the nine and the shotty / But I gotta go identify the body.” The song exemplifies a sense of moral decay and the loss of communal virtue, drawing attention to the destructive forces of systematic violence.

In “Gimme the Loot," track three, Biggie takes on a brash persona, embodying a ruthless street criminal intent on robbing people for survival and profit. The track dives deep into criminology, depicting the cycle of robbery and theft that many urban youths fall into. The violent ethos of the song is embodied in the lyrics:

Motherfuckin’ right, my pockets looking kinda tight

And I'm stressed

Yo, Biggie, let me get the vest

No need for that, just grab the fucking gat

The first pocket that's fat, the TEC is to his back

Word is bond; I'm a smoke him, yo, don't fake no moves (What?)

Treat it like boxing, stick and move, stick and move

Nigga, you ain't got to explain shit

I've been robbing motherfuckers since the slave ships

With the same clip and the same four-five

Two-point blank, a motherfucker sure to die

That's my word, nigga even try to bogard

Have his mother singing, "It's so hard"

Egoism is a dominant ethical principle within the song, with Biggie’s persona driven by self-interest and personal gain. His character sees crime as a means to an end, showing little concern for the victims. In the second verse, he raps, “From the Beretta, putting all the holes in ya sweater / The money-getter, motherfuckers don't know better / Rolex watches and colorful Swatches / I'm digging in pockets, motherfuckers can't stop it / Man, niggas come through, I'm taking high school rings too / Bitches get strangled for their earrings and bangles / And when I rock her and drop her, I'm taking her door knockers / And if she's resistant: blakka, blakka, blakka / So go get your man, bitch, he can get robbed, too / Tell him Biggie took it, what the fuck he gonna do?” Yet, the song also raises questions about utilitarianism—Biggie's logic might suggest that his actions, though immoral on an individual level, serve a purpose by providing him with what he needs to survive in a world that offers him few.

Track five, “Warning,” , my favorite song on the album, bestows a paranoid narrlative of betrayal and self-efense, where Biggie is alerted to a plot against him. The song focuses on the ever-present threat of violence in the drug trade, where one’s life is always at risk: “Damn, niggas wanna stick me for my paper!" This track speaks to the ethical dimensions of street violence, where survival justifies preemptive strikes against potential threats. He raps, “There's gonna be a lot of slow singin' and flower-bringin' / If my burglar alarm starts ringin' / What ya think all the guns is for? / All-purpose war, got the Rottweilers by the door / And I feed 'em gunpowder so they can devour / The criminals tryin' to drop my decimals / Damn, niggas wanna stick me for my cream / And it ain't a dream, things ain't always what it seems / It's the ones that smoke blunts with ya, see your picture / Now they wanna grab their guns and come and get ya.” Biggie’s reaction reflects elements of deontology, where he feels morally obligated to defend himself, even if it means killing others in self-defense. The ethical principle of virtue ethics also arises, as Biggie's street-savvy persona showcases traits such as courage, loyalty, and intelligence, seen as virtues within his world. In the final verse, he raps, “Touch my cheddar, feel my Beretta / Buck what I'ma hit you with, you motherfuckers better duck / I bring pain, bloodstains on what remains / Of his jacket, he had a gun, he shoulda packed it / Cocked it, extra clips in my pocket / So I can reload and explode on your asshole / I fuck around and get hardcore / C-4 to your door, no beef no more, nigga / Feel the rough, scandalous / The more weed smoke I puff, the more dangerous / I don't give a fuck about you or your weak crew / What you gonna do when Big Poppa comes for you?” These virtues are necessary for survival but are morally ambiguous in the context of the violence they perpetuate.

The title track, "Ready to Die," underlines Biggie's nihilistic mindset, with lyrics detailing his struggles with mental health, suicidal thoughts, and a lack of purpose. He raps, “I'm ready to die and nobody can save me / Fuck the world, fuck my moms and my girl! / My life is played out like a Jheri curl, I'm ready to die!” The song reflects the desperation and hopelessness that often accompanies life in impoverished communities, where systemic neglect and trauma drive individuals to the brink. Later in the second verse, Biggie raps, “A big bad motherfucker on the wrong road / I got some drugs, tried to get the avenue sold / I want it all from the Rolexes to the Lexus / Getting paid is all I expected / My mother didn't give me what I want, what the fuck? / Now I've got a Glock making motherfuckers duck / Shit is real and hungry's how I feel / I rob and steal because that money got that whip appeal.” The title track aligns closely with doom-ism, as Biggie expresses a belief that death is the only escape from his suffering. There’s a stark contrast between egoism—Biggie’s focus on his own suffering—and virtue ethics, which would have him find meaning in community, love, or personal growth. Biggie is driven by nihilism, rejecting societal codes and private virtues. In the final verse, he asserts,

Your face, my feet, they meet with stompin'

I'm rippin' MCs from Tallahassee to Compton

Biggie Smalls on a higher plane

Niggas say I'm strange, deranged because I put the 12 gauge to your brain

Make your shit splatter

Mix the blood like batter then my pocket gets fatter

After the hit, leave you on the street with your neck slit

Down your backbone to where your motherfuckin’ shit drip

The shit I kick, ripping through the vest

Biggie Smalls passing any test, I'm ready to die!

Track nine, “The What,” is a collaboration between Biggie and Method Man of the Wu-Tang Clan, centered on aggressive, hedonistic indulgence in materialism and power. Their lyrics reflect a philosophy of living for the moment, with little regard for the future: “Fuck the world, don't ask me for shit / Everything you get you gotta work hard for it / (Honeys shake your hips) You don't stop / (And niggas pack the clips) Keep on, bitch.” The song represents the pursuit of personal pleasure, wealth, and dominance in a society that offers few legitimate paths to success. Biggie raps,

Welcome to my center, honeys feel it deep in they placenta

Cold as the pole in the winter

Far from the inventor, but I got this rap shit sewed

And when my MAC unloads

I'm guaranteed another video

Ready to die, why I act that way?

Pop duke left mom duke, the faggot took the back way

So instead of making hoes suck my dick up

I used to do stick-ups, 'cause hoes is irritating like the hiccups

Excuse me, flows just grow through me

Like trees to branches, cliffs to avalanches

It's the praying mantis, deep like the mind of Farrakhan

This hedonistic approach underscores the ethical principle of egoism, where self-gratification is the driving force behind decisions. The track portrays a world where survival is equated with self-indulgence, with no moral qualms about the means used to achieve it.

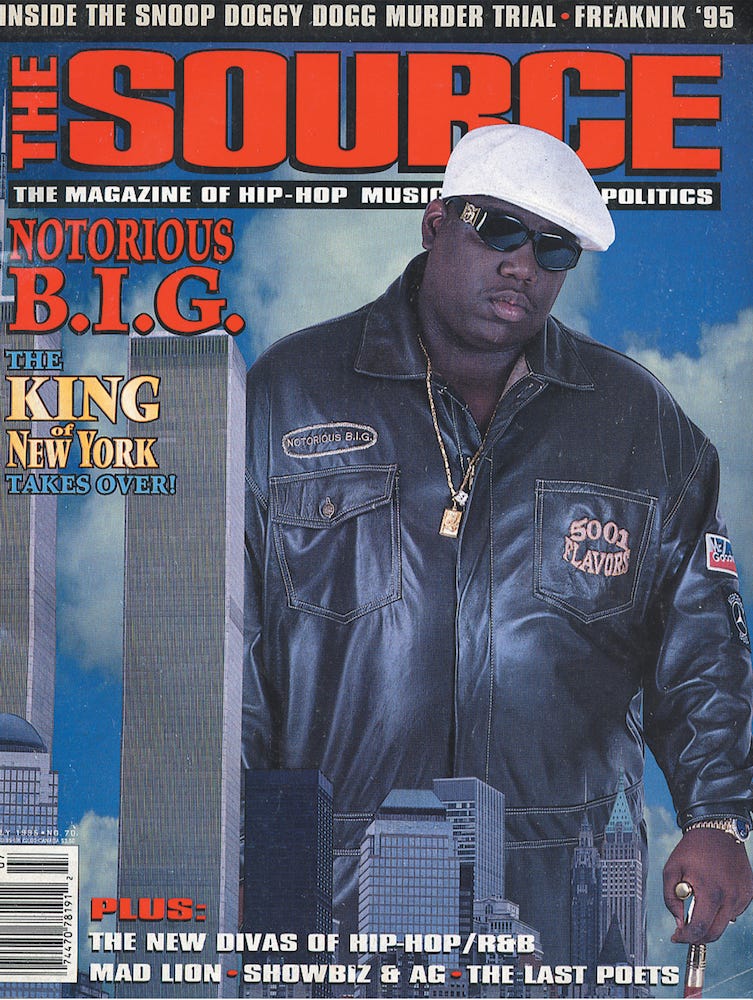

"Juicy," track ten, is the album’s most iconic and celebratory song, recounting Biggie's rise from poverty to success. The chorus, sung by R&B girl group Total, goes: “You know very well / Who you are / Don't let 'em hold you down / Reach for the stars / You had a goal / But not that many / 'Cause you're the only one / I'll give you good and plenty.” The song is a tribute to the people who helped him and those struggling in similar situations. The lyrics, “Celebrating every day, no more public housin' / Thinkin' back on my one-room shack / Now my mom pimps an Ac' with minks on her back / And she loves to show me off of course / Smiles every time my face is up in The Source / We used to fuss when the landlord dissed us / No heat, wonder why Christmas missed us / Birthdays was the worst days / Now we sip Champagne when we thirsty” highlight the transformative power of determination. Virtue ethics exists in Biggie’s depiction of himself as embodying traits like resilience and hard work, values that helped him transcend his circumstances. In the second verse, Biggie raps, “I made the change from a common thief / To up close and personal with Robin Leach / And I'm far from cheap, I smoke skunk with my peeps all day / Spread love, it's the Brooklyn way / The Moët and Alizé keep me pissy, girls used to diss me / Now they write letters 'cause they miss me / I never thought it could happen, this rapping stuff / I was too used to packing gats and stuff.” There’s also an element of care ethics, as he dedicates the song to his community, family, and friends. Biggie memorably raps, “Living life without fear / Puttin' five karats in my baby girl ear / Lunches, brunches, interviews by the pool / Considered a fool 'cause I dropped out of high school / Stereotypes of a black male misunderstood / And it's still all good.” Finally, utilitarianism is implied by Biggie’s use of his success to bring happiness and stability to those around him.

Track eleven, “Everyday Struggle,” probes the emotional toll of living in the drug trade and facing the constant threat of death or imprisonment: “I don't wanna live no more / Sometimes I hear death knockin' at my front door / I'm livin' every day like a hustle, another drug to juggle / Another day, another struggle.” In the first verse, Biggie raps,

I know how it feel to wake up fucked up

Pockets broke as hell, another rock to sell

People look at you like you's the user

Sellin' drugs to all the losers, mad Buddha-abuser

But they don't know about your stress-filled day

Baby on the way, mad bills to pay

That's why you drink Tanqueray, so you can reminisce

And wish you wasn't livin' so devilish, shit

He describes the stress of trying to survive while battling inner demons, a struggle shared by many in marginalized communities. Later in the song, Biggie raps,

I had the master plan, I'm in the caravan on my way to Maryland

With my man Two-TECs to take over this projects

They call him Two-TECs, he tote two TECs

And when he start to bust, he like to ask, "Who's next?"

I got my honey on the Amtrak with the crack

In the crack of her ass, two pounds of hash in the stash

I wait for hon to make some quick cash

I told her she could be lieutenant, bitch got gassed

At last, I'm literally loungin', black

Sittin' back, countin' double digit thousand stacks

Additionally, the song touches on deontology, where Biggie feels bound by a sense of duty to provide for his family, even through illegal means. This sense of obligation contrasts with his moral conflicts and deteriorating mental health.

On track thirteen, “Big Poppa,” Biggie celebrates a luxurious lifestyle characterized by affluence, romantic conquests, and extravagance. The song echoes a hedonistic ethic, where pleasure and sensuality are prioritized. He opens the song by rapping,

To all the ladies in the place with style and grace

Allow me to lace these lyrical douches in your bushes (Uh)

Who rock grooves and makes moves with all the mamis?

The back of the club, sippin' Moët is where you'll find me (What?)

The back of the club, mackin' hoes, my crew's behind me (Uh)

Mad question askin', blunt passin'

Music blastin', but I just can't quit

Because one of these honeys Biggie got to creep with

However, Biggie’s charm and charisma align with virtue ethics, presenting him as embodying the virtues of confidence and social prowess admired in hip-hop culture. The chorus famously goes, “I love it when you call me Big Poppa / Throw your hands in the air if you's a true player / I love it when you call me Big Poppa / To the honeys gettin' money, playin' niggas like dummies / I love it when you call me Big Poppa / You got a gun up in your waist, please don't shoot up the place (Why?) / 'Cause I see some ladies tonight that should be havin' my baby, baby.”

“Unbelievable,” track sixteen, showcases Biggie’s lyrical skill and confidence in his abilities, as he asserts his dominance in the rap game:

Live from Bedford-Stuyvesant, the livest one

Representing BK to the fullest

Gats, I pull it

Bastards ducking when B.I.G. be bucking

Chicken-heads be clucking, in my back room fucking

It ain't nothing

They know B.I.G. be handling

With the MAC in the Ac' door paneling

Bandaging MCs, oxygen, they can't breathe

This song is driven by egoism, where Biggie places himself at the center of his decent world, asserting his superiority. Later in the song, he raps,

Dumb rappers need teaching

Lesson A: Don't fuck with B-I

That's that "Oh, I thought he was wack"

Oh, come, come now, why y'all so dumb now

Hunt me or be hunted

I got three hundred and fifty-seven ways

To simmer sauté, I'm the winner all day

Lights get dimmer down Biggie's hallway

My forte causes Caucasians to say

"He sounds demented"

Yet, it also reflects virtue ethics, as Biggie’s excellence in his craft is a key component of his identity.

The closing track, "Suicidal Thoughts," is a haunting reflection on Biggie's internal suffering and contemplation of suicide:

When I die, fuck it, I wanna go to hell

'Cause I'm a piece of shit, it ain't hard to fuckin' tell

It don't make sense, goin' to heaven with the goodie-goodies

Dressed in white, I like black Timbs and black hoodies

God'll probably have me on some real strict shit

No sleepin' all day, no gettin' my dick licked

Hangin' with the goodie-goodies, loungin' in paradise

Fuck that shit, I wanna tote guns and shoot dice

The song is a stark portrayal of his mental health struggles, revealing the dark side of fame and fortune. Later in the song, Biggie expounds, “I swear to God I want to just slit my wrists and end this bullshit / Throw the Magnum to my head, threaten to pull shit / And squeeze until the bed's completely red / I'm glad I'm dead, a worthless fuckin' Buddha head / The stress is buildin' up, I can't—I can't believe / Suicide's on my fuckin' mind, I wanna leave / I swear to God I feel like death is fuckin' callin' me / But nah, you wouldn't understand.” Doom-ism is once again central, as Biggie resigns himself to a fatalistic outlook, believing there’s no escape from his pain. However, care ethics can be discerned in the raw vulnerability of the track, as it serves as a cry for help and understanding, exposing the emotional toll of his lifestyle. The song ends with Biggie somberly rapping, “I reach my peak, I can't speak / Call my nigga Chic, tell him that my will is weak / I'm sick of niggas lyin', I'm sick of bitches hawkin' / Matter of fact, I'm sick of talkin' [Gunshot].”

Upon release, Ready to Die achieved multi-platinum status within a year, showcasing its commercial success. Critically acclaimed, it received a near-perfect rating from The Source and later ranked 22nd on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list. The album's single "Big Poppa" earned a Grammy nomination for Best Rap Solo Performance at the 38th Annual Grammy Awards. MTV further recognized the album's impact by naming "Juicy" one of the greatest hip-hop videos ever. Hit singles like "Big Poppa," “One More Chance,” and "Juicy" helped reestablish East Coast hip-hop's dominance.

The album's production, overseen by Sean Combs, masterfully blended commercial appeal with street credibility. Collaborators like “Mister Cee” Calvin LeBrun, DJ Premier, and Easy Mo Bee created a sonic palette that merged boom-bap with R&B, resulting in timeless hits that balanced accessibility and authenticity.

While Ready to Die revitalized East Coast rap, it coincided with an intensifying East Coast-West Coast rivalry. As Ben Westhoff details in Original Gangstas, the rise of Bad Boy Records challenged Death Row Records' dominance, leading to a feud between former friends Biggie and Tupac.

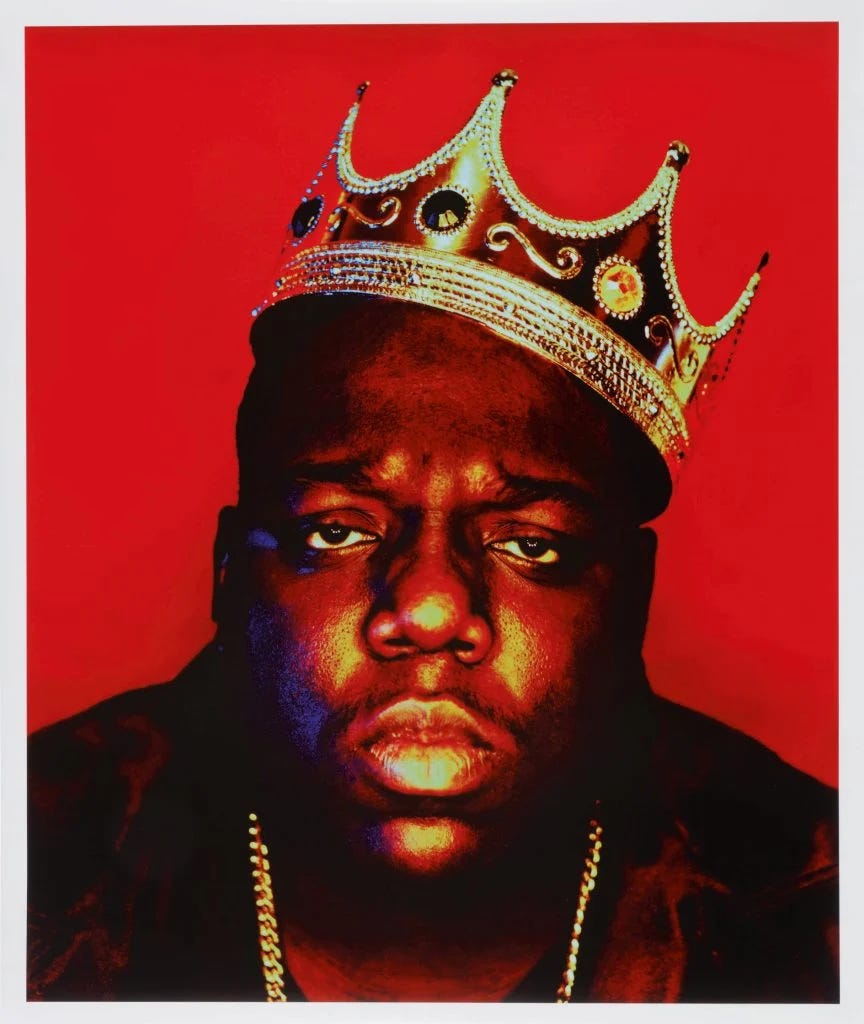

On March 9, 1997, Christopher Wallace was fatally shot in Los Angeles. His unsolved murder remains one of hip-hop's most tragic events, with books like The Murder of Biggie Smalls by Cathy Scott and Murder Rap by Greg Kading exploring various theories about his death.

Biggie's posthumous album Life After Death, released shortly after his passing, achieved diamond certification and featured hits like "Hypnotize" and "Mo Money Mo Problems." His influence inspires generations of artists, from JAY-Z to Lil Wayne.

Three decades later, Ready to Die is still celebrated as a timeless masterpiece that reshaped rap music. In 2024, the Library of Congress added the album to the National Recording Registry, recognizing its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Ready to Die’s raw storytelling and flawless production have secured its place among the greatest musical works ever created. Though Biggie's life was cut tragically short at twenty-four years old, his brief yet brilliant career left an indelible mark on music and popular culture, with his artistry continuing to resonate with new generations of listeners.